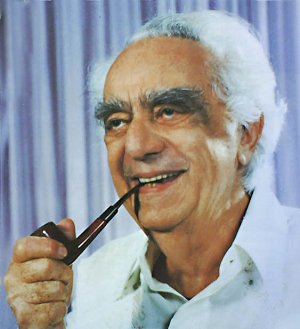

1908: The Iraqi Jew Who Would Lead Singapore Is Born

Peeved with British criticism of Singapore as a ‘pestilential and immoral cesspool’, David Marshall would become the Asian nation’s first chief minister.

by David B. Green

Mar 12, 2015

March 12, 1908, is the birthdate of David Marshall, the first head of government of a semi-independent Singapore. Although Marshall’s tenure as Singapore’s chief minister was short – 14 months – many of his ideas were adopted by later governments, and he is remembered fondly in the island nation for his integrity, passion and great patriotism.

David Saul Marshall was born in Singapore, the eldest of the seven children of Saul Nissim Mashal (the family’s original surname) and Flora Eziekel Mashal, Orthodox Jewish immigrants from Baghdad.

When he was six, David’s mother took him and his siblings back to Baghdad for a family visit. Unfortunately, World War I had begun, and the Turkish forces occupying the city put them under house arrest. They would remain in Iraq for more than three years.

On his return to Singapore, David was educated at St. Andrew’s School and at Raffles Institution, after which his intention was to claim a Queen’s Scholarship to study medicine in London. But after contracting tuberculosis, in 1925, he was instead sent to a sanatorium in Switzerland, after which he moved on to Belgium to study the business of textile manufacturing. Later he worked in the trade for a while back in Singapore before traveling to London to study law.

Who made this cesspool?

Marshall had become interested in politics years earlier, giving his first political speech at age 19, at a YMCA in Singapore. Responding to a recent statement by a British MP who called the crown colony a “pestilential and immoral cesspool,” Marshall turned to his audience and asked it rhetorically, “Who is responsible for making this cesspool?”

Much later, he said he had become a politician in order to fight the racism that he felt characterized the “’white man, brown man’ relationship… Like you call me ‘Jowdy Jew, brush my shoe,’ and next thing I know is I hit you on the nose… I wanted to break the sonic barrier against Asians and especially against Jews.”

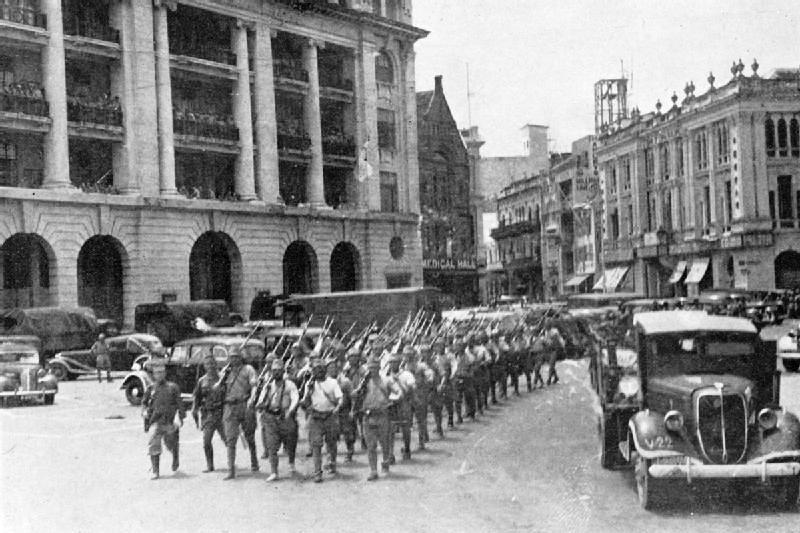

After graduating law at the University of London, he was called to the bar in 1937. The next year, following German’s invasion of Czechoslovakia, Marshall volunteered for the Singapore Volunteer Corps of the British army.

He was captured when Singapore fell to Japanese forces, in February 1942, and spent the next three years as a prisoner of war, passing through a total of 26 different camps, and for a period being forced to work in a Japanese mine in Hokkaido island.

A lot of murder suspects go free

Following his return to Singapore after World War II, Marshall began a career as a criminal defense attorney, and was an amazing success. He claimed to have won acquittals for 99 out of 100 murder suspects he defended.

When Lee Kuan Yew abolished the jury system in Singapore, in 1969, he pointed to Marshall’s record as one of the reasons for the move.

David Marshall was a staunch believer in Singaporean independence from Britain. In 1953, that goal was partially attained, with the U.K. granting domestic self-governance. The Labor Front party tapped Marshall to be its leader and went on to emerge in the lead after the first election in April 1955. Marshall was named chief minister and formed a minority government.

His period in office was marked with labor unrest and severe racial tensions. In 1956, after failing to negotiate complete independence during talks in London, he resigned.

The following year, he founded the Workers Party of Singapore, but had only limited success as its leader, and left politics for good in 1963, returning to his legal career.

In 1978, Marshall was named Singapore’s first ambassador to France, and in the years that followed, he also became envoy to Portugal, Spain and Switzerland. He retired from the diplomatic corps in 1993.

David Marshall died of lung cancer, on December 12, 1995. In its obituary, the London Independent praised Marshall as “an egalitarian, a humanitarian full of compassion, [and] a champion of the underdog,” who, “While he admired modern Singapore’s achievements … pleaded for more open political debate, a more independent-minded press, a more caring society and a kinder judicial system, free from emergency laws or capital punishment.”

Category: Personal History