A Group of Young Iraqis Risk Imprisonment to Reconnect With Their Country’s Jewish Past

by: Eetta Prince-Gibson

Seven decades after the mass Jewish exodus from Iraq, a group of intrepid Iraqis and Israelis are holding clandestine meetings and talks in a bid to rekindle ties between the two countries and their peoples

His real name isn’t Gilgamesh, hero of ancient Mesopotamian mythology. That’s just a pseudonym he and other young Iraqis use as cover for their activism. He’s afraid he will be arrested by the Iraqi authorities if they discover his group’s clandestine contacts with Israelis, including two meetings in recent years in Istanbul and Berlin.

It all started some six years ago when Gilgamesh met an Israeli, Ariel Dloomy, on a panel at an academic conference in Europe. Dloomy recalls listening to “an Iraqi man about my age, who had tremendous knowledge about the history of Jews in Iraq,” who expressed “sadness at the social and economic losses Iraq suffered when the Jews left.”

“My father, who was born in Iraq, came to Israel at the age of 13,” says Dloomy. “His memories were bitter. He told us about the Farhud [the two-day pogrom in Baghdad in June 1941, during which up to 180 Jews were killed]. He talked about his uncle, who was kidnapped by local Muslims and never heard from again. He told us that his family lost its vast property and, when they came to Israel, were relegated to a life of poverty.”

Dloomy says he was shaken to the core. “I couldn’t believe there were Muslim Iraqis who were showing empathy for the history of the Iraqi Jews,” he recounts about that first meeting.

‘Fascinated and moved’

It has been a tumultuous history. Jews had lived prosperously in Iraq since the sixth century B.C.E., but the Farhud marked the beginning of the end. In 1948, just prior to the establishment of the State of Israel, the Iraqi government dismissed Jews from the civil service, imposed quotas at universities and other institutions, and supported the bombing of synagogues. Jews were stripped of their citizenship and forced to relinquish their assets.

In September 1948, a prominent Iraqi-Jewish businessman, Shafiq Ades, was publicly hanged after a show trial in which he was found guilty of selling weapons to Israel. By 1951, almost all of Iraq’s 120,000 Jews had been airlifted to Israel.

“We both knew [our meeting at the conference] shouldn’t stay just between the two of us,” explains Gilgamesh, speaking to Haaretz via Skype. “I was fascinated and moved by the stories of what happened to the Jews after they left Iraq – and I knew they were curious about Iraqis my age and about modern Iraq.” He remembers thinking that “we could perhaps make a real contribution to changing our societies and the entire Middle East.”

Together, Dloomy and Gilgamesh decided to organize the first meeting of Israeli Jews and native Iraqis since the great exodus in the ’50s.

“We decided that Gilgamesh would bring his friends, and I would bring Israelis of Iraqi descent,” says Dloomy. “We were able to raise funding from European foundations, and we set up a meeting in Istanbul in 2014 and in Berlin in 2015.” Gilgamesh adds by way of explanation: “We choose Istanbul and Berlin because they are destinations that wouldn’t raise any suspicions among the Iraqi authorities.”

Vered Cohen-Barzilay, an educational entrepreneur who participated in both of the meetings, tells Haaretz that she joined in order “to understand my own Mizrahi roots,” referring to Jews of Middle Eastern or North African origin. “My father came from Iraq, and I have always viewed myself as part of the Middle East. To me, meeting with Iraqis about my own age, and hearing about Jewish Iraq from them, was a way to connect to my own Iraqi background.”

Cohen-Barzilay recalls that as a child growing up in Israel, she tried to distance herself from her Iraqi heritage. Like Dloomy, she recalls that her father’s experiences in Israel were difficult and bitter. Most Iraqi Jews – especially those from the larger cities such as Baghdad and Basra – were prosperous and well-educated. But when they left Iraq, they were forced by the Iraqi authorities to relinquish all their assets.

It wasn’t only that they had to adjust to newly imposed poverty. They also suffered from the widespread discrimination against Mizrahim that pervaded Israeli society, and which remains a source of tension in Israeli society to this day.

“Growing up in Israel, everything Mizrahi was considered inferior to Ashkenazi culture,” says Cohen-Barzilay, admitting she was ashamed of her background. “It has taken a full generation for Mizrahim to regain our strength and to be proud of our identity. To me, meeting with Iraqis about my own age and hearing about Jewish Iraq from them is a way to connect to my own Iraqi background.”

Making amends

Dloomy also believes that the meetings help contribute to what he refers to as a new Mizrahi discourse. “Over the past few years, most of the Mizrahi discourse has been about blaming the Ashkenazi establishment. We need to construct a different way of telling the Mizrahi story in Israel. This is a constructive Mizrahi discourse that asks, Can Mizrahim in Israel play a different role in creating new relationships in the Middle East by connecting to their past?”

He also feels that through meeting with Iraqi Muslims his own age who listen to the Israelis’ stories with empathy and regret, “We have an opportunity to create a corrective experience for our families – who suffered so much in their last years in Iraq and then when they came to Israel.”

Gilgamesh says his motivation stems from his own desire to make amends for the Iraqi Jews’ suffering, and also to promote multiculturalism and tolerance in his own country – which has been rocked by turmoil since the Iraq War began in 2003.

He explains that fear of the Islamic State group motivates young Iraqis like himself to yearn for a return to social diversity. “What happened to the Jews [in Iraq] has happened to other religious minorities, and will continue to happen – to Assyrians, Kurds, Shia, Turkmen, and others. The attempt to make Iraq into a homogenous state, without minorities, led to the abuses by ISIS. People realize this now,” he says.

Indeed, in a recent survey on Brothersirq – an Iraqi website with some 1.7 million users, many of them young and well-educated – some 77 percent of 62,000 respondents to a survey said they favored allowing the Jews to return to Iraq, along with reinstatement of their citizenship and return of at least some of their property.

And Israel’s Foreign Ministry has a Facebook page aimed at Iraqis, called Israel in Iraqi, with thousands of followers.

Dr. Ronen Zeidel is deputy chairman of the Center for Iraq Studies at the University of Haifa and a leader of the Iraqi-Israeli group (although he himself is not of Iraqi descent). He recounts how, at the 2010 graduation ceremony of the Department of Hebrew Language at Baghdad University, a female graduate performed the songs of Israeli singer Sarit Hadad, and the audience went wild in delight. “All of this, along with the tremendous growth in Iraqi literature dealing with Israel, points to the change in Iraqis’ views of Israel since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003,” Zeidel says.

The Iraqi-Israeli meetings, especially the meeting in Berlin, were emotionally and politically significant, says Cohen-Barzilay. “In Berlin, we met with so much loss. The Holocaust, of course. But also during a visit to the Pergamon Museum, which holds so many Iraqi treasures, one of the Iraqis saw a design in a display. He took off his shirt to show that he had tattooed that same design on his back and shoulders years ago, as a sign of Iraqi pride. So little is left in Iraq after all the years of colonialism.”

There were joyous moments, too. “We danced together, sharing the beat, wrote poetry in Arabic and Hebrew and realized how much we have in common,” Cohen-Barzilay adds.

The group members continue to maintain contact through WhatsApp, though Iraqi law forbids any contact between Iraqis and Israelis – which could lead to arrest and even charges of treason. “I am making the group public now because, despite Iraqi government policy, Iraqi citizens – especially the young – have positive feelings toward Jews and are ready to dialogue and break down the stereotypes,” Gilgamesh says.

Cohen-Barzilay is also the founding coordinator of the MENA Forum, an initiative to create a network of authors and poets in the Middle East and North African region. A talk she gave at a forum meeting in London, in which she described her personal feelings as a Mizrahi woman in Israel, was subsequently published in Iraq and went viral on Iraqi social media.

“This proves,” she says, “that literature is the only way to break the cycle, to tell our stories as individuals and as peoples from many different angles … so readers can feel less intimidated and experience, at least vicariously, what we are experiencing in our group,” she says. “Literature is a way to turn individual experiences into societal change.”

Win-win situation

Zeidel also emphasizes the diplomatic and international importance of the meetings. “Iraqis have little interest in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and Iraq is also a supporter of the Arab Peace Initiative – which calls for Israeli recognition of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, in exchange for normalization of relations with all Arab states,” he says.

“Israel and Iraq could both benefit from improved relations,” he continues. “Iraq is the second largest exporter of oil in the world, after Saudi Arabia, and could be a significant trading partner. Iraqis are desperate for Israeli aid in many areas, including construction and agriculture. Changing the relationship with Iraq could change the entire equation of relationships in the Middle East.”

Dloomy agrees. “Our dialogue takes place at the level of civil society and as private individuals. We have no pretensions to solve the Israeli-Arab conflict, but our meetings could contribute by creating a different set of relationships in the Middle East.

“I envision similar networks of connections between Israelis whose parents fled other Arab countries and people their own age from those countries. It’s a long process, and it’s very fragile, but I believe we are proving it can happen,” says Dloomy.

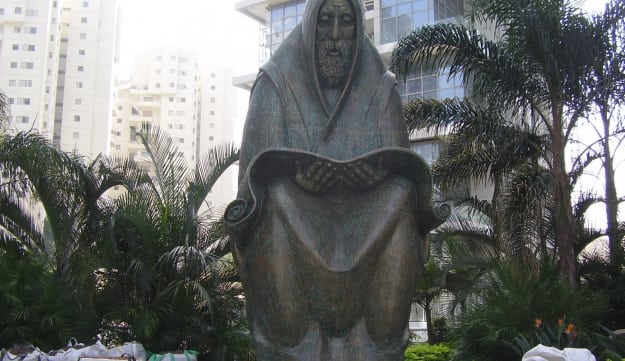

Gilgamesh even hopes to see Israeli tourists visiting Iraq, where there are many historical sites of Jewish significance. The modern city of Mosul, for example, is associated with the ancient city of Nineveh, and many believe it is the site where the prophet Daniel is buried. Tradition locates the tomb of the prophet Ezekiel in the small town of Kifel, near Baghdad.

However, given the unstable situation in Iraq, tourism to the country remains almost nil. Still, Gilgamesh believes Israelis and Jews could alter that situation. “Israeli and Jewish tourists have reasons to visit our country, and this would be good for our economy and for relations within the Middle East,” he says.

Cohen-Barzilay notes that the motivations of the Israelis participating in the meetings differ from those of older Jews who were born and raised in Iraq. “Some of the first generation, those who fled Iraq, may see themselves first as Iraqis. I see myself first as an Israeli Jew, and we will have to discuss not only the Farhud and the troubled history – but also the present, and the relationship between Israel and Iraq today.”

Gilgamesh, meanwhile, acknowledges that the distinction between being Jewish and being Israeli confused the Iraqis. “At first, I thought that many Jews would want to come back to Iraq to help create a new, pluralistic Iraq. I did not distinguish between Judaism and Zionism, or between Israel as a Jewish state and the policies of the Israeli government. It is important that we try to create a space to understand these complexities.”

He concludes, “I am fearful and yet, at the same time, I believe that nothing will destroy my dream of a new Iraq and peace among peoples in the Middle East.”

[ original here ]

Category: Iraq