I Left Iraq but Iraq Never Left Me

Jewish Exiles Finally Begin to Tell Their Story

Sephardi Voices, an Israeli audiovisual documentary project, aims to retell the story of Jewish civilization to include ‘the richness of Sephardi Jews’

By Eetta Prince-Gibson [for Haaretz.com]

Jun 13, 2017 Sitting in her airy, light-filled home outside of Jerusalem, surrounded by a garden and wide views of the Judean Hills, Linda Menuhin says thoughtfully, “I left Iraq more than 40 years ago. But Iraq never left me.”

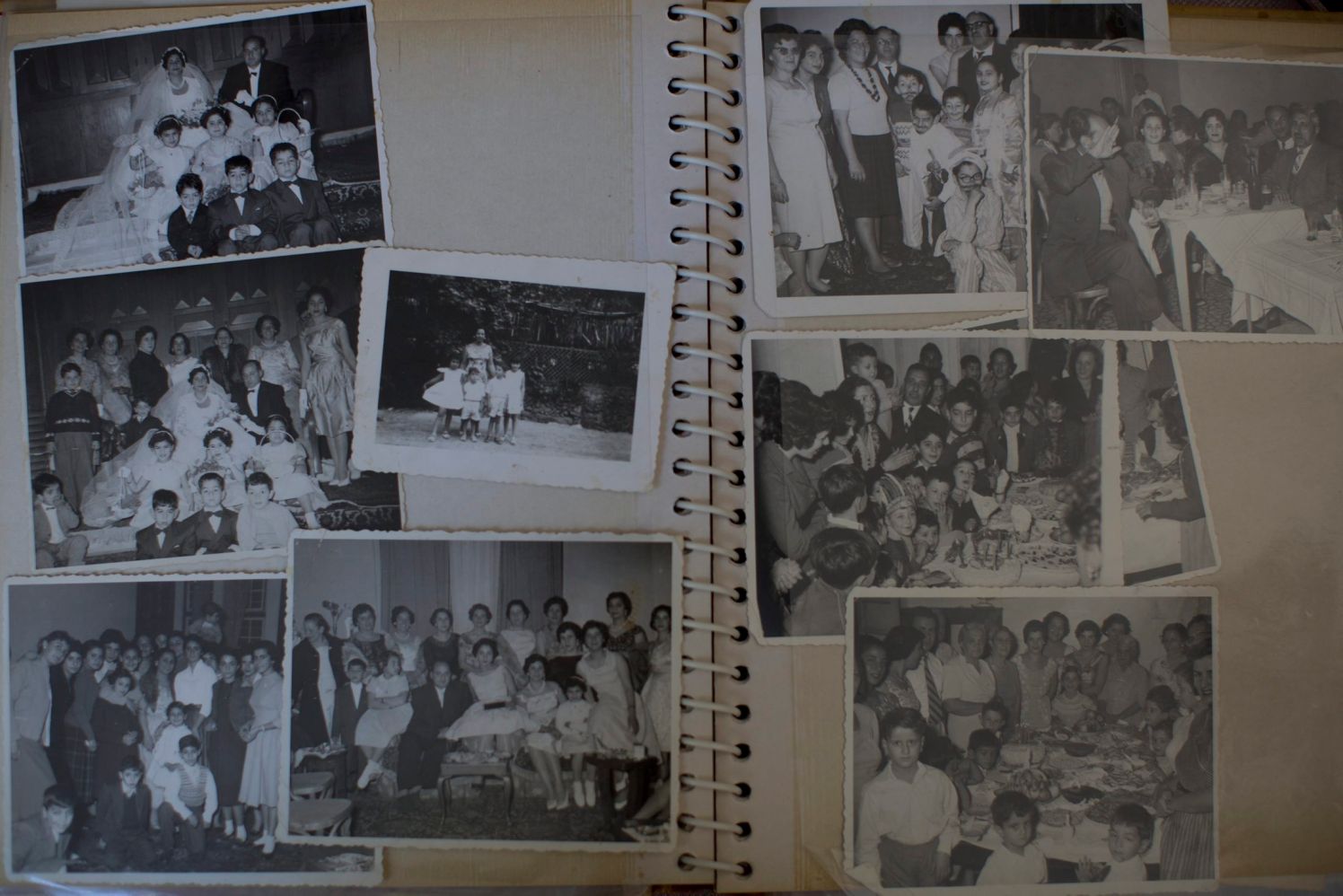

Menuhin, 67, was recently interviewed for Sephardi Voices, an ongoing project designed to create an audiovisual documentary archive of life stories, photographs and artifacts of Sephardi and Iranian Jews.

Menuhin reveals that throughout her career she had been a radio and television reporter, an intelligence analyst with the Israeli police and a consultant to various ministries. “Since I was born and raised in Iraq, my Arabic was fluent and much of my career was based on that,” she says. “But because of my experiences there, I was so hurt I had shut down and couldn’t really think about life there. I had to heal. It took me years to open up.”

It’s that opening up that Henry Green, professor of religious studies and executive director of the Sephardi Voices project, seeks to capture. “Jews lived in North Africa, the Middle East and Iran for millennia,” says Green, who was recently in Israel to interview and film for the project.

“Most referred to themselves as Arab Jews and most were well integrated into their societies. But beginning in the 1940s, Jews began to experience discrimination and violence, much of it stirred up by the Zionist enterprise. In the years following the establishment of the State of Israel, more than 95 percent of Sephardi Jews were victimized, traumatized and scattered throughout the world. And no one was telling their story.”

Founded in 2009, Sephardi Voices is modeled after Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation Institute at the University of Southern California, which has recorded the oral histories of tens of thousands of Holocaust survivors. “My research shows that it takes three generations for a traumatized community to find its voice, gain perspective and really begin to tell their story,” Green says. “The Sephardi model has been even more delayed, especially in Israel, because they are a minority within a minority.”

The project builds on “Iraq’s Last Jews,” a collection of stories of “daily life, upheaval and escape from modern Babylon” co-edited by journalist Tamar Morad and Robert and Dennis Shasha, Iraqi Jewish businessmen in the United States. Published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2008, the book was recently released in Iraq in Arabic.

In Israel with Green, the project’s media director David Langer told Haaretz that he has designed a particular look for the project, which included filming and photographing the subjects in black and white. “The project enables individuals to tell their stories and their parents’ and grandparents’ stories,” Green says. “On a macro level, the goal of the project is, in a way, to retell the story of Jewish civilization so that it will include the richness of Sephardi Jews, too.”

The project is currently focusing on Iraqi Jews. “After a long and illustrious history in Iraq, including the formulation of the Talmud, most of the Iraqi Jewish community left Iraq in the early 1950s, with a few staying until the 1980s and beyond,” Dennis Shasha said in an email. “The good and the bad stories of that last generation need to be told. That’s what we’re doing.” Shasha, with his brother Robert Shasha, is funding the project.

The 1941 “Farhud” marked the beginning of the end of the millennia-old Jewish community in Iraq. This massive two-day pogrom in Baghdad, which started during the holiday of Shavuot, killed over 180 Jews and injured 1,000. Nine hundred Jewish homes were destroyed.

After the start of Israel’s War of Independence in 1947, the Iraqi government dismissed Jews from the civil service, imposed Jewish quotas at universities and other institutions and arrested increasing numbers of Jews. Bombings targeted synagogues, but Jews were allowed to emigrate only if they first relinquished all of their assets. In 1948, a respected Jewish businessman was publicly hanged on charges of selling weapons to Israel – even though he was an outspoken anti-Zionist. By 1951, a majority of Iraqi Jews – some 105,000 – had been airlifted out of Iraq and brought to Israel.

Some, like Menuhin’s family, stayed put. She was born in 1950 into the atmosphere of increasing tension and terror. She tells her story vivaciously, with ready laughter and self-mockery, but hers is a story of loss.

“After the Six-Day War, I really began to feel afraid,” she recalls. “The authorities called in the father of a friend of mine ‘for questioning’ – and brought his body back in a sack. We were living in terror. In 1969, nine innocent Jews, accused of spying for Israel, were publicly hanged in Baghdad. I remember seeing their bodies.”

“I loved Baghdad, my community, the cosmopolitan atmosphere, the foods, the sounds, the sights. But I knew I couldn’t stay anymore,” she says.

By then, Jews could not legally leave Iraq. Against her parents’ wishes, Menuhin secretly escaped with her brother, guided by smugglers who first took them to Iran and eventually to Israel. Her mother left soon afterward and joined them there. But her father, a well-known Baghdad attorney, did not want a clandestine departure.

“As an attorney, my father believed in the law and would not leave illegally,” she says. On the eve of Yom Kippur in 1972, on his way to the synagogue, Menuhin’s father was taken into custody by the Iraqi authorities. He was never seen again.

Menuhin made her own documentary film, “Shadow in Baghdad,” about her search for her father. “We know nothing of what happened to him. We have never even said Kaddish,” she says, referring to the mourner’s prayer.

In contrast to Menuhin, identical twins Herzl and Balfour Hakak were only 2 years old when they were brought to Israel with their families, and their stories focus on the difficulties of immigration.

They are interviewed for Sephardi Voices in Herzl’s small Jerusalem apartment filled with heavy furniture and damask curtains, and located in an increasingly ultra-Orthodox neighborhood. Despite the heat, the brothers are dressed in an old-world style, in open-collar suits.

“When we came, we were told to shed our Iraqiness. The schoolbooks that we learned from mainly described the towns in Europe, the halutzim,” Herzl says, referring to the pioneers. “There was no description of the Jews from the East. But we couldn’t shed our identity, even though we were so young when we arrived. Identity isn’t something you can just cut and paste.”

Both brothers grew up to be civil servants and both are published poets, writing mostly about life in Iraq and the challenges faced by their parents and grandparents, the first generation of immigrants. “Our grandfather’s and father’s generation couldn’t express themselves,” Herzl says. “But the generation of the grandchildren and children – that is, us – can, and we can write their pain.”

He chooses to read a poem he wrote about integration into Israeli society. He clearly knows the poem by heart, yet holds the volume in front of him, as if reading to the camera.

The sundial on Jaffa Street is excited on its side

Yearning for its shadow, to those returning, to their crushing

To the sound of their shoes.

And we were redemption to its heart, a gushing crack

The whispering of the prayer

We shined and set from it and to it, to correct

The world

And I still come there, father, and I have no words

And no correction.

(Translated from the Hebrew)

Balfour adds, “When my grandfather made aliyah to Eretz Yisrael, he was in exile. Not a physical exile, of course, but he was alienated, a stranger, he didn’t belong. I write about that exile.”

He, too, reads from a book:

My grandfather is a sad king,

Born in silk and embroidered clothes, joyful clothes

And when he exiled into a country,

His clothes were destroyed, his honor was destroyed.

Only in death was he dressed in a shroud like a prayer shawl

A prayer shawl he inherited from his father,

Imprinted in blue, holy letters.

And along the prayer shawl I imagined to see

Beautiful gold stripes, distilled light,

My grandfather, Murad, son of Rafael Hakak.

(Translated from the Hebrew)

“Identity,” Balfour concludes, “is a combination of location and time. If you are only connected to the location, your identity is horizontal, flat …. If a person wants to know his identity, the answer is in this axis of time that preceded him.”

Other videos, available on the project’s website, tell the story of the ritual burial of the priceless, ancient Torah scrolls that were found destroyed in Saddam Hussein’s flooded bunker by the American forces and attempts by the older generation to inculcate their legacy in their children and grandchildren.

Green had hoped to interview Salim Fattal, known among members of the community as “the custodian of the memory of the Farhud.”

“Even though he was the director of Israel’s Arabic broadcasting service and created popular Israeli TV programs, the Farhud was the defining event of his life,” says Morad, the journalist, who is coordinating the project in Israel as a volunteer.

But Fattal, 87, died in late May.

“The elderly Iraqi Jews are dying out, and their memories are fading. This is why this is project is so urgent,” Green concludes.

Iraqi Jewish Voices, a part of the Sephardi Voices project, will officially launch in New York City in September.

[ original here ]

Category: Heritage, Personal History