Nazi Germany and the Farhud in Iraq

The most traumatic event in the collective memory of Iraqi Jews — the Farhud — took place during Shavuot 1941. During these violent riots in Baghdad thousands were raped and/or wounded, Jewish shops and synagogues were plundered and destroyed, and a staggering 180 people were brutally murdered. This unprecedented attack on the theretofore flourishing, peaceful Jewish community of Baghdad is generally thought of as triggering Iraqi Jewry’s Aliyah to Israel.

Seldom do we ask how such a pogrom could have occurred in a place where Jews had lived quietly for centuries, in a country that had not, up until that moment, been known for anti-Semitism.

A closer look at the historical background of the Farhud reveals a complicated web of factors that led to the pogroms — the opposing interests of the Iraqi government and the British Empire; Nazi Germany’s underlying influence; varying Arab movements; and internal struggles between groups of Iraqi intellectuals. The unfortunate Jews were caught in the middle of this growing conflict.

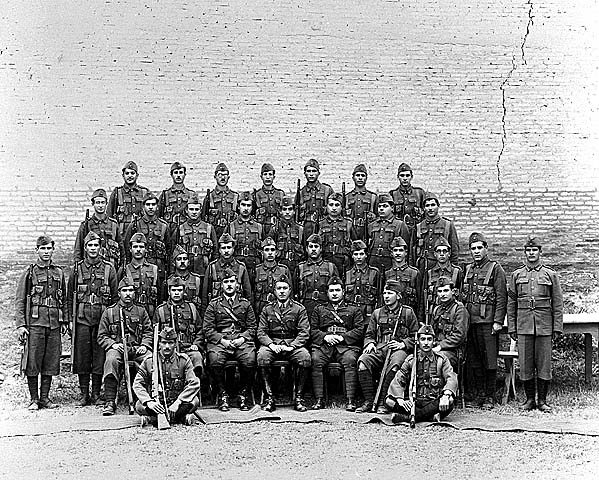

Group of young Jews who fled Iraq for Eretz Israel following the 1941 Farhud pogrom in Baghdad. They reached Eretz Israel after considerable difficulties, including arrest, trial and imprisonment by the British authorities as well as deportation. Photo: Moshe Baruch, Ramat Hasharon. Beit Hatfutsot, the Oster Visual Documentation Center, courtesy of Moshe Baruch.

In his research on Iraqi Jewry, historian Nissim Kazzaz puts the Farhud in historical context. Until the 1920s there were no significant recorded demonstrations of anti-Semitism in Iraq. In fact, in the early 20th century, restrictions from the Ottoman era were abolished, and, following World War I, the establishment of the British mandate improved the situation of Iraqi Jews.

The war, however, had other consequences. The Iraqi elite was introduced to the protocols of the Elders of Zion, texts that had been partially translated from Russian into Arabic. New and conflicting movements were rising in Iraq. Some believed that, as long as the Jews did not hold national aspirations, they were a part of the Iraqi nation. Others, such as the Al Istiklal, felt differently. Perceiving the Iraqi nationality to be Muslim Arab, they refused to accept religious minorities. Formally, after Iraq became independent from Britain in 1932, Jews were citizens of Iraq. There were voices, however, that spoke out against their integration.

At the same time, the world was experiencing profound changes. Fascist leaders such as Hitler and Mussolini were on the rise in Europe and had significant supporters among the Iraqi elite. The British expected certain privileges following Iraqi independence, such as the ability to transport goods through Iraq, which Iraqi nationalists would not concede. The nationalists insisted that Iraq establish close ties with Germany rather than be exploited by Britain.

The Germans encouraged Iraq’s support. “Mein Kampf” and Hitler’s speeches were translated into Arabic, and German educators came to Iraq to spread anti-Semitic propaganda. Iraqi newspapers became vocally pro-Germany, especially post-1939. They asserted that Iraqi Jews and Zionists were one and the same, that the world’s Jewry was scheming to ruin the glorious nation of Iraq and that Iraqi Jews must be banished from public life. With help from the Germans, and inspired by the Hitler–Jugend movement, the extremist Al-Fatwa movement was founded, calling for strict Islamic adherence by all Iraqi citizens. Eventually all students and teachers were forced to join the movement, including Jews. In 1939 the mufti, Haj Amin al-Husseini, settled in Iraq and began promoting a pro-German agenda while spreading damaging anti-Semitic propaganda.

The tension broke on April 1, 1941. Until that day Iraq had refrained from assisting the British, but also from directly assisting Germany. But Iraq’s Prime Minister, Rashid Ali, had decided it was time to change alliances. He led a coup and overthrew all pro-British officials. He then announced that Iraq would no longer provide Britain with airplane fuel, and even set Iraqi forces loose on British bases in Iraq. By the end of April the British attacked the Iraqi army. By then the Iraqi air force was manned by German Luftwaffe pilots.

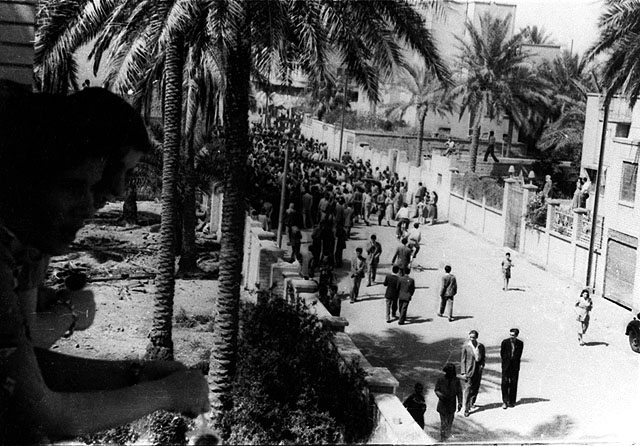

Otniel Margalit collection, photo archive, Yad Ben Zvi

In May, with help from the Irgun in Palestine, among others, the British fought the German-Iraqis forces. Finally, with support from India’s army, the British were able to defeat their foes, and on May 30th all pro-German Iraqi officials escaped to Iran. Their successors signed a surrender agreement.

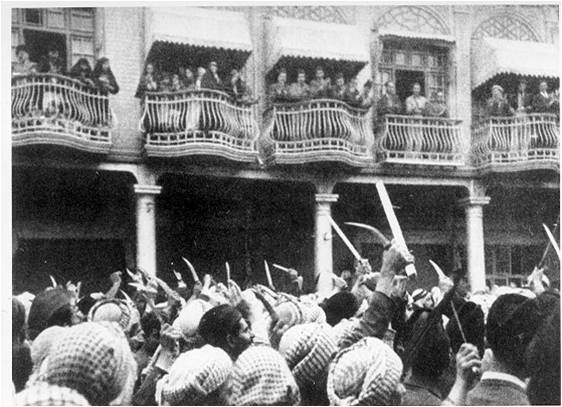

From that moment, the Jews were in imminent danger. The surrender agreement stated that the British would enter Baghdad within two days. The Al Fatwa saw a window of opportunity to incite the masses and take their anger at losing to the British out on the Jews. They marked Jewish houses in red, and on June 1st an angry mob rioted against the Jews for the first time in Iraqi history. From the newly born to the elderly, no Jew was safe. The rioters used all manner of weapons, including running people over with their vehicles. Some Jews were rescued by Muslim neighbors who refused to join the mob. These Muslim resisters hid Jews, at great risk to their own safety. The massacre only ceased when the British entered the city and stopped it. Sadly, the British knew about the pogrom a day prior, but made no attempt to prevent it. Just like the local authorities, they preferred to let the masses take their rage out upon the Jews.

After the Farhud, the Iraqi authorities held an investigation, blaming nationalistic elements and even executing a few army officers who were involved in the incitement. Haj Amin al-Husseini was named in the investigation, and Germany’s involvement was eventually recognized. Despite the erecting of a monument in Baghdad in honor of the victims, the Farhud triggered mass Jewish emigration from Iraq. Ten years later, as part of Operations Ezra and Nehemiah (1950-1952), some 120,000 Jews — 90% of Iraqi’s Jewry — chose to leave Iraq for the young state of Israel.

Category: Baghdad