Return of Jewish artifacts to Iraq sparks outrage

Who is the rightful owner of a stunning collection of Iraqi Judaica known as the Iraqi Jewish Archives: the descendants of that country’s exiled Jewish community now living in the United States, or the Iraq government that stole the material from its Jewish population in the first place?

That is the question as the National Archives in Washington, D.C. readies an exhibit titled “Discovery and Recovery: Pre-serving Iraqi Jewish Heritage.” Originally scheduled to open Friday, Oct. 11, it will open once the federal government shutdown ends.

Over several decades, successive regimes in Iraq systematically destroyed the country’s 2,500-year-old Jewish community and expropriated its property — right down to the last ancient prayerbook and Torah scroll.

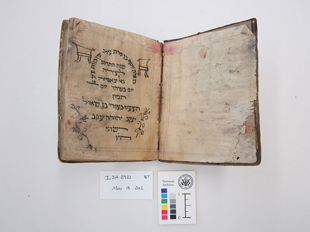

Torah case from mid-19th to early 20th century

For years, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein stored it all in the basement of his secret police headquarters. Until the 2003 U.S. invasion, the material — thousands of documents and artifacts, including everything from Jewish day school records to rare editions of the Talmud — moldered away.

In May 2003, 16 American soldiers searching for biological and chemical weapons entered the building, and there in the basement, amid four feet of water, they found the waterlogged treasures of the Jewish community.

A vanquished Iraq made a deal with U.S. occupying forces to allow some of the material — more than 2,700 Jewish items altogether — to be taken to the United States for restoration, preservation and digitization. Some 300 Torah scrolls were left behind.

The United States agreed to return the materials to Iraq in 2014 in exchange for a promise that the Iraqi antiquities ministry would take good care of them.

But the Iraqi Jewish community in the United States is having no part of it.

In advance of the exhibition, Justice for Jews from Arab Countries (JJAC) and Jews Indigen-ous to the Middle East and Africa (JIMENA) have launched a campaign to prevent the archives from returning to Iraq where, they believe, the materials will either rot or be destroyed.

“The archives were looted by the Iraqi government from the Jewish community,” said Gina Waldman, executive dir-ector of the S.F.-based JIMENA. “We hope the U.S. government will bar the return of the archives to Iraq, and do everything possible to [reach] a mutually agreeable, fair and just agreement so that the Iraqis are encouraged to hand the archives to the rightful Jewish owners.”

Stanley Urman, executive vice president of JJAC, cites the legal principle “jus ex injuria non oritur,” which in international law means that a state cannot assert legal rights to property illegally obtained. “[The materials] were seized from Jewish institutions, schools and the community. There is no justification or logic in sending these Jewish archives back to Iraq, a place that has virtually no Jews, no interest in Jewish heritage and no accessibility to Jewish scholars.”

Haggadah from 1902, hand-lettered and decorated by an Iraqi youth photos/u.s. national archives and records administration

According to former Pentagon analyst Harold Rhode, who was with the U.S. military when it discovered the materials in 2003, international law forbids a nation from removing the patrimony of another country, even when captured in war.

But he contends that these particular treasures were never Iraq’s to begin with, and he castigated the United States for promising to return them.

“The Iraqi government ‘acquired’ this material by stealing it from the Jewish community and by persecuting a minority religious population,” he wrote in a post at PJMedia.com. “It is the Iraqi government which has no provenance. It is stolen property.”

Charles Goldstein disagrees. As counsel to the Commission for Art Recovery, he is an expert on restitution of Holocaust-looted art. Though personally sympathetic to JIMENA and its allies, Goldstein said they have no legal standing to demand the materials remain in the United States.

“This is not a legal issue,” he said. “It is not normally a violation of international law when a country takes property from its own citizens. That may be different if you can prove discriminatory taking without compensation, which may be the case here, but each individual [owner] would have to make a claim. A claim cannot be made by the Jewish community abroad.”

Waldman said JIMENA made no claim to the archives, but countered, “The agreement [between the United States and Iraq] was based on a flawed premise that the archive is part of Iraq’s national heritage, which it is not. It is the patrimony of Iraqi Jews and it must be returned to its rightful owners.”

JIMENA board member Joseph Dabby feels he could be one of those rightful owners. Born in Baghdad in 1946, Dabby says his school records may be among the archives’ documents. He attended Jewish schools, and later became a civil engineer before fleeing the country in 1971.

Some of his friends were not so lucky. In a spasm of maniacal anti-Semitism, many Iraqi Jews were publicly hanged, accused of being spies for Israel.

Dabby made his way to Los Angeles, where he lives today. A member of Kahal Joseph Congregation, which boasts mostly Iraqi Jews as members, he insists the archives stay here.

“This is part of a Jewish community that no longer exists,” he said. “I feel it should be returned to us in diaspora. Why would we return these [materials] to them? Are we really going to believe they will be taken care of? I would like my children to be able to see things that would make them proud of their history.”

Category: Heritage, Iraq, Preservation Promotion Education

By

By