The first Jews in Canada

Jewish immigrants on board the General Stugis arrive in Halifax in 1948.

When Canada first became a country, 150 years ago, there were slightly less than 1,200 Jews living here. But Jewish settlement in French, and then British, North America, goes back much further.

In 1677, Joseph de la Penha, a young Sephardic Jewish merchant, ship owner and financier of privateers from Rotterdam, Netherlands, landed on the coast of Labrador and claimed the territory for the Stadtholder William of Orange. Some years later, one version of this story goes, when William became King William III of England, de la Penha saved the king from drowning during a stormy sea voyage. Another version has it that one of de la Penha’s ships had protected the English coast from attack by the French in 1696. In any event, to show his gratitude, William bequeathed de la Penha all of Labrador. This generous gift was confirmed in an official document in 1697.

More than three centuries later, in 1927, when the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ruled that Labrador belonged to the then colony of Newfoundland, Isaac de la Penha, the cantor at Montreal’s Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue and one of Joseph de la Penha’s direct descendants, filed a lawsuit claiming Labrador for the family. The case stalled, but was restarted in 1950 by a group of de la Penha’s descendants in Europe and Israel. Nothing came of that, either. Then, in 1983, Daniel de la Penha, a retired physician in South Carolina who was also a descendant, launched a third claim for part of Labrador in the Newfoundland courts. After losing his first challenge, he appealed to the province’s Supreme Court. Alas, Newfoundland chief justice Alex Hickman ruled that de la Penha did not have sufficient proof “that he was entitled to a piece of Labrador.” De la Penha appealed his case to the Supreme Court of Canada, but the court refused to consider it.

Catholic pre-revolutionary France absolutely forbade non-Catholics – including Huguenots, other French Protestants and Jews – from settling in New France and most other overseas colonies. Still, large numbers of Huguenots managed to immigrate to the Antilles during the 17th century, and some, at least briefly, made it to New France, as well. So, too, did a handful of Jews.

The most well-known story of a Jew attempting to settle New France is the tale of 23-year-old Esther Brandeau, except she tried to elude the authorities disguised as a young man named Jacque La Fargue. Once she arrived in Quebec in 1738, she decided that continuing her charade was not practical and revealed her true identity as a Jewish woman. At first, she declared her intention to convert to Catholicism, yet within a few months, she began to have second thoughts, which aggravated the intendant (the colony’s chief administrator), Gilles Hocquart. By the fall of 1739, Hocquart, annoyed by her “frivolity” and “stubbornness,” deported her back to France, where she vanished from the historical record.

Determining who was truly the first Jew to call Canada home is a toss up between two entrepreneurial traders: Samuel Jacobs, a resourceful merchant and accomplished fiddle player, and Aaron Hart, the patriarch of the celebrated Hart (originally Hertz) family, whose illustrious members appear so prominently in the annals of Quebec. In this contest, the historical evidence suggests that Jacobs was most likely “Canada’s first Jewish settler,” yet Hart can claim the title of the “father of Canadian Jewry,” as Denis Vaugeios, the Hart family’s biographer has argued.

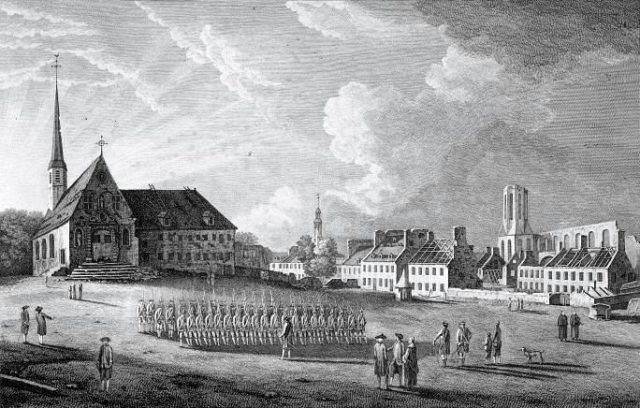

A Jesuit cathedral in Quebec circa 1761. Catholic pre-revolutionary France forbade non-Catholics, including Jews, from settling in New France. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Like many of their Jewish contemporaries in British North America, both men were born in central Europe, probably in the early 1720s – Jacobs in Alsace and Hart in Bavaria (or possibly England). As young Dorfjuden – village Jews of Ashkenazi ancestry, who spoke German, Yiddish or English – both these men came to North America in search of economic opportunities, adventure and the relative freedom that was offered to Jews in the British colonies.

Jacobs and Hart journeyed to North America and found work as purveyors to the British army during the Seven Years War in the years before the British conquest of New France in 1759-60. Supplying the armies of Europe was a profitable enterprise that attracted numerous Jewish merchants during this era. Yet Jacobs, Hart and other Jewish merchants who wound up in Nova Scotia and Quebec after 1760, had to make their way in a Christian world – a world filled with prejudice, discrimination and innumerable obstacles.

Both Jacobs and Hart were assimilated and not overtly religious. (It goes without saying that truly observant Jews would have stayed in Europe with established Jewish communities, synagogues and access to kosher food). Jacobs, like some of his other fellow Jewish traders, married a French-Canadian Catholic woman, Marie-Josette Audet dit Lapointe, while Hart returned to England to seek a Jewish wife, Dorothea (or Dorothy) Judah, his cousin. Both had large families and sons who caused them headaches. Hart was by all accounts more conscious of his Jewish religious duties, though Jacobs had a rudimentary understanding of the Hebrew language and often signed his name as “Shemuel.” Swept up in the times, the vast majority of both of their descendants did not end up remaining Jewish. (This did not include Cecil Hart, the great-great-grandson of Aaron Hart, who coached the Montreal Canadiens in the 1930s. In 1923, his father, Dr. David Hart, donated the Hart Trophy, to be awarded to the “player judged most valuable to his team.” After Cecil died in 1940, the trophy was renamed the Hart Memorial Trophy in his honour.)

Aaron Hart was one of the first Jews to settle in Canada.

Jacobs moved from New Brunswick to Quebec by 1760. Settling along the Richelieu River in Saint-Denis, he prospered as a merchant and landowner. Jacobs, who died around 1786, did not belong to a synagogue, nor did he ever make a donation to the synagogue in Montreal. He raised his children as Christians. Yet, he never stopped thinking of himself as a Jew. “I was disputing all last night with a German officer about religion,” he wrote a non-Jewish friend in 1778. “I am not a wandering Jew, yet I am a stirring one.” In other words, there was no commercial challenge or issue that scared him.

Based in Trois-Rivières by 1762, Aaron Hart enjoyed life as a pioneer aristocrat until the day he died in late 1800. He also was a successful merchant, landowner and wisely invested in the fur trade, partnering with other Jewish traders. Unlike Samuel Jacobs, Hart and his wife raised their large family in a Jewish home, as much as that was possible in Trois-Rivières.

In August 1763, Frederick Haldimand, the military governor of Trois-Rivières, had to appoint an English-speaking postmaster in a predominately French-Canadian village. The choice came down to a selection between what he described as “a Jew, a (British) sergeant and an Irish soldier on half pay.” He selected the Jew, Aaron Hart – “my Jew,” as he referred to him. This appointment meant that Hart was in all probability the first Jew to hold a public office in Quebec after the British had assumed control of the territory.

Historian and writer Allan Levine’s next book, Seeking the Fabled City: The Canadian Jewish Experience will be published in 2018 by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada.

[original here]

Category: Canada