TRADITIONS Of Their Own

New York’s Iraqi Jews follow customs that originated far from Eastern Europe

By Elicia Brown (freelance writer)

April 26, 2003

[edited and corrected July 2017]

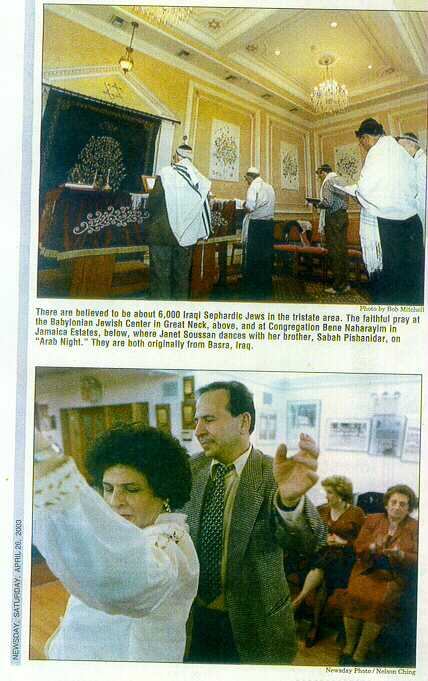

In the narrow hallway outside the synagogue office, Joyce Raby Reiss slowly twirled her hands high in the air, gyrating her wrists. Her eyes sparkled. On the dance floor, a woman wiggled her shoulders, and two little girls jumped in pajamas. Onlookers clapped and sang. It was Arabic night last week at Congregation Bene Naharayim in Jamaica Estates, and for many the music evoked the magic of childhood in Baghdad.

In the narrow hallway outside the synagogue office, Joyce Raby Reiss slowly twirled her hands high in the air, gyrating her wrists. Her eyes sparkled. On the dance floor, a woman wiggled her shoulders, and two little girls jumped in pajamas. Onlookers clapped and sang. It was Arabic night last week at Congregation Bene Naharayim in Jamaica Estates, and for many the music evoked the magic of childhood in Baghdad.

“It’s emotional food for your soul,” said Reiss, 54. “It transports you back.”

Reiss, who lives on the Upper East Side, arrived in the United States as a teenager at a time, she said, when American Jews appeared uncomfortable with Jews who identified with Arabic music or language. But as recent events allow her to consider a first trip back to her birthplace, she reflects that she’s no longer without means to celebrate her cultural identity in New York.

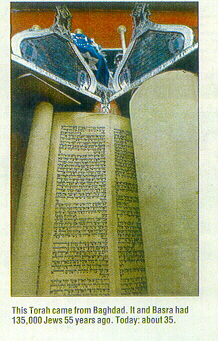

It is a cultural identity rooted in the 2,700-year history of Jews in the Fertile Crescent. The first large community was established after the Babylonians destroyed the Kingdom of Judah and forced about 40,000 Jews to resettle in the land that is modern-day Iraq. At its height 55 years ago, the community numbered 135,000, centered in Baghdad and Basra, but today only about 35 remain, said Maurice Shohet, president of Bene Naharayim.

Since the first Iraqi Jews made their way to New York a century ago, their numbers have grown to as many as 6,000 in the tristate area, community members say – making them perhaps the largest Iraqi immigrant group in New York.

Unlike most American synagogues, which belong to the Ashkenazi (Eastern European) branch of Judaism, Iraqi Jews adhere to their own traditions [Minhag Habibli]. They founded an aid society for new immigrants in the tristate area in 1934, purchased a cemetery section at New Montefiore in West Babylon in 1945 and, three years later, formed a club like those at which Jews had socialized in Baghdad. The tight-knit community established two synagogues: Bene Naharayim and an offshoot, the Babylonian Jewish Center in Great Neck, in 1998.

Although the Iraqi Jews here don’t always comply with Orthodox Jewish standards of religious observance, their synagogues most closely affiliate with Orthodox practice, said Shohet, 52, of Great Neck, a systems management analyst. “We call ourselves traditional.”

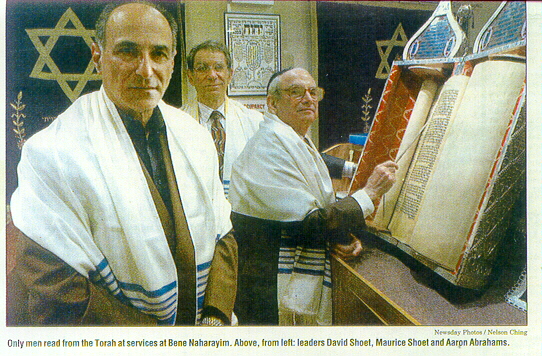

During religious services, men and women sit separately, and only men can be called to read from the Torah. “When you’re inside the synagogue, you observe,” said Aaron Abrahams, who serves as the cantor and religious adviser of Bene Naharayim. “Whatever you do outside is your business.”

For example, Saeed Herdoon, 66, a Merrick resident who belongs to the Babylonian Jewish Center, said he says the blessing over wine every Friday night when he and his wife share a traditional Shabbat dinner, but on Saturday afternoons he sometimes takes in a movie.

Reiss said she rarely goes to services, preferring more personal prayers, but when she does seek out a house of worship, she said, “none of the services speak to me except the Iraqi Jewish ones.”

Bene Naharayim, founded in a ranch-style house on Midland Parkway, has a mailing list of 432 family names. It was there, 13 years ago, that Reiss’ son, Alexander, marked his bar mitzvah, or “bar miswah,” as it is called in the colloquial tongue of Iraqi Jews, an Arabic dialect laced with Hebrew and Turkish words.

The Babylonian Jewish Center’s 250 members already need more space, said the synagogue’s president, Albert Nassim, 67, of Great Neck, and expect to add a new wing soon.

In each synagogue a hard, cylindrical shell encases the Torah scrolls, and worshipers read the text from an upright position rather than rolling it out on a table as in the Eastern European tradition. When a man is called for an aliyah – to read from the Torah – he makes a donation to the synagogue, another custom that differs from Eastern European practice.

In each synagogue a hard, cylindrical shell encases the Torah scrolls, and worshipers read the text from an upright position rather than rolling it out on a table as in the Eastern European tradition. When a man is called for an aliyah – to read from the Torah – he makes a donation to the synagogue, another custom that differs from Eastern European practice.

The customs of Iraqi Jews are known as Minhag Baghdadi, or Minhag Habibli, meaning Babylonian in Hebrew. Since he came to this country in 1969, Abrahams, a native of Calcutta, has led services in the traditional manner of his Iraqi ancestors. At first, this entailed singing once or twice a year at various Manhattan hotels for the Jewish High Holidays.

The prayers of Iraqi Jews feature several distinct sounds, including a “w” absent in the spoken language of Israel today and a strong “h,” almost like a gasp for air, rather than the modern Hebrew “ch,” which is sometimes compared to a throat-clearing noise. The Iraqi Jews’ pronunciations would have sounded authentic to Jews 3,000 years ago, Abrahams explained at the Arabic night party.

But some Iraqi Jews here wonder how long their traditions will continue – despite their country’s having served as the center of Jewish life in the Dark Ages and having produced the Babylonian Talmud.

At Arabic night in Bene Naharayim, where the median age was about 65, the only woman under 40 in attendance brought her two young daughters because “they love coming here.” The 24-year-old woman is a second-generation American, but she’s taught her girls to dance to Middle Eastern music and makes sure they get a chance whenever possible to eat “grandma’s kouba,” a type of ground meat sometimes coated in a rice shell.

But the woman, who didn’t want her name published, said she doesn’t know how to cook the dish herself. “I know it’s bad. The traditions are so few with my generation.”

Although Reiss said she’s happy that her son, now 26, grew up in the United States – where he’s “pretty much guaranteed a good life” – he doesn’t “get into the music the way I do. And this is not comfort food for him,” she said, looking down at the buffet of rice flecked with raisins and almonds, chopped cucumber and tomato salad, and rosewater-infused baklava.

“I feel a tremendous sense of loss,” she said. “When those of us in our 40s and 50s are gone, it will all be gone.”

Still, Reiss said the fall of Baghdad deeply moved her son, a research assistant at a Manhattan financial institution. As for herself, Reiss said she sobbed for an hour this month after watching Iraqis celebrate in the same square where the bodies of nine Jewish classmates had dangled in 1969. They had been hung on charges of spying for Israel. “Their souls and ghosts were there,” Reiss said. “God’s wheels turn slowly but surely.”

Still, Reiss said the fall of Baghdad deeply moved her son, a research assistant at a Manhattan financial institution. As for herself, Reiss said she sobbed for an hour this month after watching Iraqis celebrate in the same square where the bodies of nine Jewish classmates had dangled in 1969. They had been hung on charges of spying for Israel. “Their souls and ghosts were there,” Reiss said. “God’s wheels turn slowly but surely.”

Copyright © 2003, Newsday, Inc.

[edited and corrected July 2017]

Category: Minhag Bavel