An AlQosh Man Struggles to Keep a Promise to an Old Friend

By Amer Hedow

AlQosh, IRAQ – Abandoned since 1948 by native Iraqi Jews remains the tomb of the Jewish Prophet Nahum, a minor prophet in the Hebrew Bible. Nahum wrote about the Assyrian Empire and the plains of Ninevah and prophesized the fall of Assyrian Kingdom for failing to turn from their pagan ways.

AlQosh, IRAQ – Abandoned since 1948 by native Iraqi Jews remains the tomb of the Jewish Prophet Nahum, a minor prophet in the Hebrew Bible. Nahum wrote about the Assyrian Empire and the plains of Ninevah and prophesized the fall of Assyrian Kingdom for failing to turn from their pagan ways.

Nahum was written after the fall of Israel in 722 BC but before the fall of Ninevah in 612. It is very likely, based upon the description of the relationship between Assyria and Judah, that Nahum prophesied in the early reign of King Josiah. Assyria was in the last days of its great power. They still controlled most of the Middle East. However, Babylon, Persia, and Egypt were all expanding in strength.

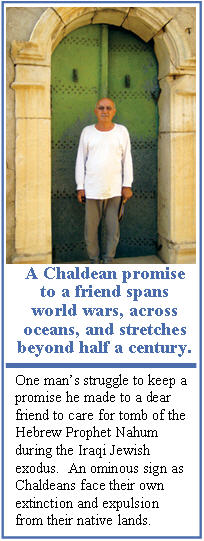

Literary enthusiasts would appreciate the irony that the tomb has been gently cared for and preserved by native Iraqi Christians. After Iraqi Jews were forced to leave their country over half a century ago due to their religious difference with the prevailing Muslims of the region, Sami Jajouhana was asked to be the keeper of Nahum’s tomb. He was handed the iron keys and an old leather ledger by his Jewish friend who left al-Qosh in 1948. Jajouhana promised his dear friend to care for the sacred site for Jews.

Beneath one of the few remaining standing synagogues in all of Iraq, Nahum’s tomb is at risk. For over half a century, few Jewish pilgrims have journeyed to the site. Nonetheless, Jajouhana keeps his promise to his old friend, by recording the few who do tour the tomb or visit the synagogue and to care for their holy place. Jajouhana has handled the landscaping, cleaned the vandalism that often plaques the monument, and managed repairs the best he can with the minuscule resources his family has in honor of his friendship and his friend’s convictions.

The building is crumbling and in need of major repairs. Most of the roof’s supporting beams and some stone walls have deteriorated. The Hebrew scripture is unmistakably visible on the interior walls—square, precisely carved, unobtrusive and definitively Hebrew. All at risk to be forever lost except for this one man on a mission to rebuild.

“He says it is his duty as a man and his virtue of a promise to his Jewish friend and the Jewish people,” says Jajouhana’s village neighbor. “Iraq used to be a country of many different flowers and this synagogue remains a garden we must care for in hopes the flowers will once more grow.”

The scant visitors in the ledger show a handful of visitors in the past decade. Some are Jewish academics and tourist, most are American soldiers traveling from Camp Freedom, 30 miles south near Mosul.

AlQosh used to be home to thousands of Jewish families. Jajouhana takes reporters on a tour through his village streets pointing out Jewish homes that were occupaied for over a thousand years, but have been abandoned for over the last fifty years. “Moishe, Saida, Sarah, Machea, Zacchaeus, Naji, Maurice,” Jajouhana recites, names of childhood friends he said “wanted to go, and they have now all died.” The last to leave, a rabbi and his family, lived directly across the narrow street from the entrance to the synagogue of Nahum.

Jews settled in ancient Nineveh near the site of present-day Mosul after Shalmaneser, king of Assyria, conquered Samaria in about 730 b.c. In 1165 Benjamin of Tudela found 7,000 Jews living in Mosul. By the beginning of the 20th century scholars say their population had dwindled to between 1,000 and 4,500. Now the Jews of Nineveh cannot be found.

Further south near present-day Baghdad, the Babylonians led into captivity 18-year-old King Jehoiachin and thousands from Judah in 598 b.c. By the latest estimates, there are eight Jews in Baghdad, all elderly. They represent the entire Jewish population of what was once the largest Jewish diaspora in the world (Deuteronomy 28:25). As recently as 1904 Jews made up an estimated 30 percent of Baghdad’s population—40,000 people—and led the city’s cultural pursuits and commerce.

It is a common misperception—and one currently on exhibit at the U.S. State Department website—to link Jewish migration in the Middle East to the Holocaust, and to portray those who have settled modern-day Israel as outsiders, pretenders, or invaders. Little is said about the Jews forced out of their Arab homelands throughout the previous century, most notably since the creation of Israel, when 870,000 Arab Jews, known as Mizrahi, came to Israel as refugees.

Although Jews had lived in Mesopotamia 1,000 years by the time the Islamic armies conquered it. Jews in AlQosh by the 1930s lived under laws restricting their travel, employment, and education. With the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Iraqi Jews faced wholesale discrimination and if ever accused of being Zionists, the death penalty.

It’s no surprise that those not forced out simply left when given the opportunity. Jewish quarters across the Middle East—in Cairo, Damascus, and elsewhere—emptied. And the trend continues: This month the first of about 100 Jews from Yemen are scheduled to arrive in New York as refugees.

Chaldeans are familiar with the same sort of attrition. Iraq’s native and historic Christian churches are being emptied and systematically destroyed, their population halved since the U.S. invasion. And, as last month’s bomb attacks on six churches demonstrated, pressure to leave comes from persistent violence and threats, if not by legal mandate.

But those who suffer are not only those who are persecuted. “Even the Muslims need historical references,” said Antoin Odo, head of the Chaldean bishops of Syria and a man who traces his family roots to AlQosh. Christians—and Jews—he told me, “represent something that comes before them.” The fear is that by eradicating the true history of Iraq, fanatics will attempt to rewrite history and re-educate the masses into a dark future of intolerance and hatred.

In his own little way, anchored in the Christian virtue of keeping ones word to a dear friend, Jajouhana shines a beam of light both into the past and into the future. Jajouhana has reached out to Chaldeans in Europe and America asking for help in raising funds to rebuild the Jewish monument.

Inquiries on setting up a foundation to preserve the site are being explored by Chaldean groups in both Europe and America, but nothing has materialized. Chaldean community leaders in Michigan’s chapter of the Chaldean Justice League have reached out to Jewish community leaders in hopes of creating a joint-culture effort to save the AlQosh synagogue.

“He wishes the garden of Iraq blooms with all the beautiful flowers it once had.” Says Jajouhana’s neighbor.

Category: Iraq, Justice for Jews of Arab Countries