Baghdadi Jews in Early Shanghai

by Maisie J. Meyer

Many Baghdadi Jews (the term “Baghdadi” in this context encompasses Arabic speaking Jews from the Middle East, Aden and Yemen, and non-Arabic speaking Jews from Persia and Afghanistan) emigrated to escape political and religious harassment and deteriorating economic conditions in their countries of origin. Their search for new commercial opportunities brought them to a string of trading posts as far a field as London, Bombay, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. Their experience in Shanghai was distinctive in the Asian Baghdadi diaspora, not least because of their efforts to “rescue” the remnants of the Kaifeng Jewish Community. In the course of time Shanghai Baghdadi Jews were hugely outnumbered by Ashkenazi victims of persecution that found refugee in the ten square miles of the British dominated foreign concessions of Shanghai.

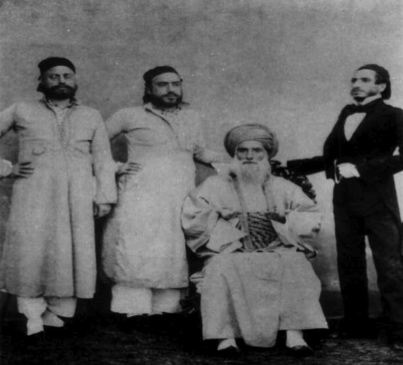

Elias Sassoon (1820-80), the son of David Sassoon (1792-1864), patriarch of the Baghdadi Jews in Bombay, and a scion of the illustrious family of Baghdad, in ca. 1845 pioneered the settlement of Baghdadi Jews in Shanghai, a port opened in 1842 after the First Opium War. Ten square miles of Shanghai was set aside for foreign residence and in time evolved into the International Settlement. Within five years the Sassoon firm established offices in Hong Kong and along the entire China coast and monopolized the most lucrative part of the China-India trade and later between England and East Asia. Elias purchased land at incredibly low prices which in time rose astronomically. After 1895 the firm established spinning and weaving plants, and rice, paper and flour mills.

The Sassoons recruited office managers, clerks and warehouse men from Baghdad and India to work in their China offices, and Shanghai became a major centre of Sassoon operations, second only to Bombay. The firm safeguarded Baghdadi Jewish traditions which were crucial in maintaining their identity throughout the century of their sojourn in the foreign concessions of Shanghai. Initially, accommodation was provided for their staff. No business was done on Sabbath and festivals and services were held adhering to Baghdadi customs (minhagim). Employees were taught how to slaughter poultry in the ritual manner to ensure they had kosher food when they traveled. Their kinship, their religious traditions, their practice of endogamy, similar commercial interests, and not least their distinctive cuisine provided bonds with their kinsman elsewhere in the Baghdadi diaspora…

Commerce

Baghdadi merchants, lured by the lucrative China trade, were undeterred by the arduous journey to Shanghai, which in the 1870s was an unsanitary, overcrowded city that experienced frequent outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. Sassoon employees generally went on to establish their own export and import businesses, mainly dealing in tea, silk, cotton and opium. In the early and mid-nineteenth century Jews filled numerous intermediary roles in the British controlled opium trade, which was made legal in China after the conclusion of the Second Opium in 1860. They made huge fortunes by exporting opium produced in India to China in exchange for tea and other commodities, which were then shipped to England. The damaging effects of the drug caused increasing moral pressure to be applied on the British government during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. When many English companies ceased dealing in opium, Baghdadi merchants legitimately continued the trade, which didn’t end until 1917, but became targets of trenchant criticism mainly from missionaries.

Baghdadi Jews were only a tiny minority in the vast ethnic milieu in which they settled, but they nonetheless participated in almost every aspect of business and professional activity. The end of the century saw Baghdadis take a high profile in banking, public utilities, the stock exchange, real estate markets and industrial development. Although they never numbered more than 1,000 they made a considerable impact on the growth of the treaty port. Marcella Crohn Rubel, an American visitor to Shanghai in 1925, recorded that half the business and residential areas were in the hands of Baghdadi Jews who had made their fortune in the Orient. (IM, October 9, 1925, 7)

The splendid landmark Cathay Hotel (now the Peace Hotel) was hailed as the “Claridges of the East” when it was completed in 1929. It was the pride of its owner Sir Victor Sassoon, grandson of Elias the founder of the community. The Sassoon, Ezra, Hardoon, Benjamin and Somekh buildings located in the heart of the city, to say nothing of their palatial homes, notably Sir Eli Kadoorie’s Marble Hall (now the Children’s Palace, an arts and craft centre), are today monuments to a once vibrant community particularly as their tombstones and cemeteries no longer exist. These entrepreneurs helped fashion Shanghai into a city which in 1932 was recognized as the fifth largest in the world. Israel’s Messenger, the journal of Shanghai Baghdadi Jews, labeled it “the Tel Abib [sic] of the Orient.” A small proportion, notably the Sassoons, Kadoories, Ezras, Shahmoons, Benjamins, Hayims and Josephs were conspicuously wealthy and rose to an unparalleled level of commercial achievement, but the majority of Baghdadi Jews were impoverished and found work in the great companies founded by fellow Jews.

Interaction with the Kaifeng Jews

Life in the treaty port had the trappings of colonialism and … the British official attitude was to censure foreigners associating with the indigenous population. A rigid set of self-enforced rules demarcated social boundaries … In this context, the heroic efforts of Baghdadis to rescue the remnants of the Jewish community of Kaifeng … are remarkable.

Shanghai Jews collected funds to rebuild the Kaifeng synagogue, employ efficient teachers, mohalim to perform circumcisions, and shochatim to provide ritually slaughtered meat, in order to put Kaifeng Jews “upon a footing to do credit to our religion … let us now become parents and guardians to these poor brethren.” (Philip Cowan Papers (PCP) June 23, 1902) They offered to help them to come and settle in Shanghai where they and their families would be maintained. Some eight Kaifeng Jews came to Shanghai and were shown a good deal of Jewish life, witnessed Jewish ceremonies, frequented the synagogue and visited several Jewish homes. S. M. Perlmann, a scholarly merchant, records an interview with some of them whom he perceived to be of “low intellect and lacking education,” yet able to read the Bible, “thanks to instructions they had received at Shanghai.” (Perlmann 1913, 11) He was struck by the astonishment of the Chinese servants seeing these Chinese Jews treated with the same civility extended to other guests.

In time, however, the ardor of the Shanghai Baghdadi Jews cooled because of the inaccessibility of Kaifeng, inadequate resources, [and] the fact that nothing of lasting value was accomplished … The turning point in the commitment of Shanghai Jews to rescue the remnants of the Kaifeng community came in July 1937 at the start of the Sino-Japanese Undeclared War, when the community became absorbed with protecting their own interests and any vestige of concern they may have had for their Kaifeng coreligionists disappeared completely.

Interaction with Jewish Refugees in Shanghai

Baghdadi Jews also demonstrated their solidarity when Russian Jews escaping the press gangs and Czarist persecution and revolution came to Shanghai mainly via Harbin (Manchuria) in four waves; between 1895-1904, 1905-17, 1932-34 and 1937-39. At their peak there was a ratio of 4-6000 Russians to some 1000 Baghdadis. (Kranzler 1988, 57-65). A fund set up for their relief illustrates the feeling of responsibility Baghdadis felt towards them…

By the end of 1939, relief committees manned by amateurs established a network to attend to the basic needs of some 16,000 refugees. Wealthy Baghdadis were at the helm of the relief work. Sir Victor Sassoon provided housing for some 2,500 newcomers when virtually no accommodations were available. He endowed large sums for a Rehabilitation Fund which loaned money to refugees to set up business, and was generously supported by other wealthy Baghdadis. Given Shanghai’s economic problems following the outbreak of war in July 1937, it was no mean feat that they enabled numerous refugees to become self-supporting and also employ other refugees. The Kadoorie School which opened in January 1942 was equipped to accommodate 600 refugees with seventeen teachers. Its high academic standard is attested to by many of its pupils who became successful businessmen and professionals. In gratitude they and numerous Baghdadi Jews in 1997 dedicated a memorial in Israel to its founder and mentor Horace Kadoorie…

When the Japanese occupied the foreign concessions of Shanghai at the outbreak of the Pacific war in December 1941, they classified Baghdadis who were British subjects as “first-class enemy nationals.” They were interned in civilian assembly centers where they were underfed and housed in painfully cramped conditions. Others were categorized as “second-class enemy nationals,” were required to wear armbands and their movements restricted. Foreign owned houses or apartment blocks were requisitioned and troops moved into many spacious houses owned by Baghdadis. A large number of Baghdadis employed in British and American companies lost their jobs, or were obliged to work under Japanese management. With their assets confiscated and bank accounts virtually frozen, it became impossible to conduct private business and many Baghdadis were reduced to selling their valuables to subsist. Several families became destitute. In this way, the community became fragmented and unable to reconstitute itself.

The End of the Community

After the Pacific War, the treaty port where capitalism and western influences had dominated for a century gradually began to change from an exciting liberal and cosmopolitan metropolis. The authorities treated all foreigners as “despised imperialist parasites.” When the Communist Peoples’ Liberation Army came into Shanghai in May 1949, the attachment of Baghdadi Jews to the city they had regarded as their permanent home was replaced by an urgent desire to leave as soon as possible, even if it meant sacrificing their investments and business interests. Ironically, the Baghdadis who had acted as host to vast numbers of refugees were pressured to leave Shanghai in the late 1940s and early 1950s as refugees in search of homes in the newly founded State of Israel, Australia, England, America and Canada…

The reasons for the demise of the Baghdadi community after a century in Shanghai are complex. The process of disintegration set in, no doubt, with the Japanese invasion of the Chinese areas of Shanghai and the curtailment of economic life. It continued under Japanese wartime occupation and then by a strange twist of fate, they were pressured to leave their “homeland.” They left with few possessions, but with their identity intact…

Excerpted from her essay “Baghdadi Jews in Shanghai”.

Reference and Further Reading

Books

Bickers, Robert A. 1999 Britain in China: Community, Culture and Colonialism 1900-1949. Manchester University Press; New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Cohen, Israel. 1925. The Journal of a Jewish Traveller. Plymouth: Mayflower Press.

Jackson, Stanley. 1968. The Sassoons. New York: E.P. Dutton.

Meyer, Maisie J. 2003. From the Rivers of Babylon to the Whangpoo: A Century of Sephardi Jewish Life in Shanghai. Lanham, New York, Oxford: University Press of America.

Perlmann, S M. 1913. The History of Jews in China. London: Mazin.

Pollak, Michael. 1980, 1983, 1998. Mandarins, Jews and Missionaries. New York, Tokyo: Weatherhill.

Roland, Joan G. 1989. Jews in British India: Identity in a Colonial Era. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England for Brandeis University Press.

Roth, Cecil. 1941. The Sassoon Dynasty. New York: Robert Hale.

Timberg, Thomas A. ed. 1986. Jews in India. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House.

Articles

Betta, Chiara, “Silas Aaron Hardoon (1849-1931), Marginality and Adaptation in Shanghai,” Ph.D. dissertation, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1997.

—— Betta. 2000 “Marginal Westerners in Shanghai: The Baghdadi Jewish Community 1845-1931,” in Bickers and Henriot eds., New Frontiers: Imperialism’s New Communities in East Asia 1842-1953. Manchester.

Eber Irene. 1993. “Kaifeng Jews Revisited: Sinification and Affirmation of Identity,” Monumenta Serica, 41.

——– Eber. 1999b. “Kaifeng Jews: Sinification of Identity” in Jonathan Goldstein, ed., The Jews of China: Historical and Comparative Perspectives Vol.1. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Knowles, Christopher. 1992. “The Sephards of Shanghai”, China Review.

Leslie, Donald D. and Meyer, Maisie J. 1995. “The Shanghai Society for the Rescue of the Chinese Jews,” in Albert Dien (ed.), Sino-Judaica: Occasional Papers of the Sino-Judaic Institute 2.

Meyer, Maisie J. 1999 “Baghdadi Jewish Merchants in Shanghai and the Opium Trade”, Jewish Culture and History Volume 2, No. 1, Frank Cass Journal.

——–Meyer. 1995a. “Three Prominent Sephardi Jews,” ed., Dien, Sino-Judaica.

——– Meyer. 2000b. “The Sephardi Jewish Community of Shanghai and the Question of Identity” in Roman Malek ed., From Kaifeng … to Shanghai. Jews in China, Monumenta Serica Monograph Series 46. Sankt Augustin.

——– Meyer. July 2001c. “The Inter-relationship of Jewish Communities in Shanghai,” Immigrants and Minorities., Volume 19, A Frank Cass Journal.

——– Meyer. forthcoming. “Baghdadi Jews, Chinese “Jews” and Chinese” paper submitted at the International Symposium, “Youtai – Presence and Perception of Jews and Judaism in China”, Germersheim, Germany 2003.

Roland Joan, “Baghdadi Jews in India,” Sino-Judaica 4 (2003).

Editor, Yutkowitz, “Shanghai Fortunes,” Jewish Monthly, 101, no.7. (March, 1987).

Category: China, Minhag Bavel