Jews in Shanghai

by Steve Hochstadt

I Jews in Colonial Shanghai

One of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the world, Shanghai in the late 19th and early 20th century was an international banking city and the gun-running capital of Asia, a center for trade in textiles and opium, an open port where law was subordinated to profit.

After the British navy defeated Chinese forces in the Opium War of 1842, two large sections of central Shanghai became autonomous foreign entities: the International Settlement dominated by British and American business interests and governed by the Shanghai Municipal Council, and the French Concession run by the French government through its Consul General.

The extraterritorial governments controlled police, customs, and judicial matters in the two settlements. Shanghai became a capitalist paradise. Western businessmen controlled downtown Shanghai, with its great banks, port facilities, hotels, and warehouses. The Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC) was elected by the tiny proportion of foreigners who owned substantial property. Extremes of wealth and poverty jostled in the crowded streets.

Some of the earliest British subjects in Shanghai were Jews who originated in the Middle East. A few of these Baghdadi families became enormously wealthy and joined the financial elite in Shanghai, including the Sassoons, Kadoories, and Hardoons. In the early 20th century, poorer Baghdadi Jewish families fled from conscription in the Ottoman Turkish army. By the 1930s the Baghdadi community numbered nearly 1000. They congregated in the Ohel Rachel synagogue, built in 1920, and sent their children to the Shanghai Jewish School.

The other Jewish community in Shanghai had come from Russia, refugees from Tsarist anti-Semitism, and then from revolutionary upheaval and Stalinist terror. They were more numerous, numbering about 5000, but not as well off as the Baghdadi Jews. The Ohel Moishe synagogue, opened in 1907 in Hongkou, served this Ashkenazi community.

During the early 20th century, the Japanese became the largest foreign colony in the city. The Japanese military occupied Manchuria in 1931-1932, and then battled the Chinese army in Shanghai for several months in 1937, destroying large parts of the Hongkou district. Fighting continued until February 1938, by which time the Japanese were the dominant military power in Shanghai. They controlled customs, post, and telegraph, and they took over police powers in Hongkou, officially part of the International Settlement. They demanded more voice in the SMC and its police forces, but did nothing to challenge the extraterritorial privileges within the International Settlement.

II Refugees from the Nazis

During the first five years of Nazi persecution, from 1933 to 1938, about 130,000 of the 525,000 Jews living in Germany left the country. Through the end of 1937, however, only about 300 Jewish refugees had arrived in Shanghai. Michael Blumenthal, who later became Secretary of the Treasury under President Jimmy Carter, had this to say about the choices refugees faced:

It was sort of a hierarchy of things. If you went to the United States, that was a good thing. If you went to England that was a good thing. If you went to another European country, it was fine, to Holland, to France, all that was good. If you went to New Zealand and to Australia and then to Canada, that was good. There were countries that were considered to be okay. Brazil was okay, Argentina and Uruguay were okay, maybe Chile. There were countries that were considered to be not so okay, Paraguay and Bolivia, because they were considered to be primitive countries in which it was difficult to make a living, where a European wouldn’t be happy. Dominican Republic, Panama, certain Central American countries were considered to be semi-desperation countries you went to. And the worst place was Shanghai.

The level of desperation of German Jews was not yet great enough to overcome their disinterest in moving to China.

On 12 March, the German armed forces marched into Austria, and the Austrian population responded to this Anschluss with an orgy of violence against Jews, especially in Vienna. In June, the Evian Conference of 32 nations ended without taking any action to increase opportunities for Jews to emigrate. No nation welcomed Jewish refugees; anti-Semitism was a worldwide disease.

Then, on November 9 and 10, 1938, the so-called Kristallnacht, a carefully organized national pogrom attacked Jewish synagogues, businesses and people. Thirty thousand men were taken to Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Buchenwald. With great difficulty family members discovered that a ticket out of the country could get their men out of concentration camp. The illusion that Jews could somehow manage to find an accommodation with the Nazis government was destroyed by the end of 1938. German Jews left the country in 1939 at four times the rate of the years before 1938. The combination of desperation to flee and the lack of desirable places to go suddenly made Shanghai an acceptable choice for thousands of Jews in the Third Reich.

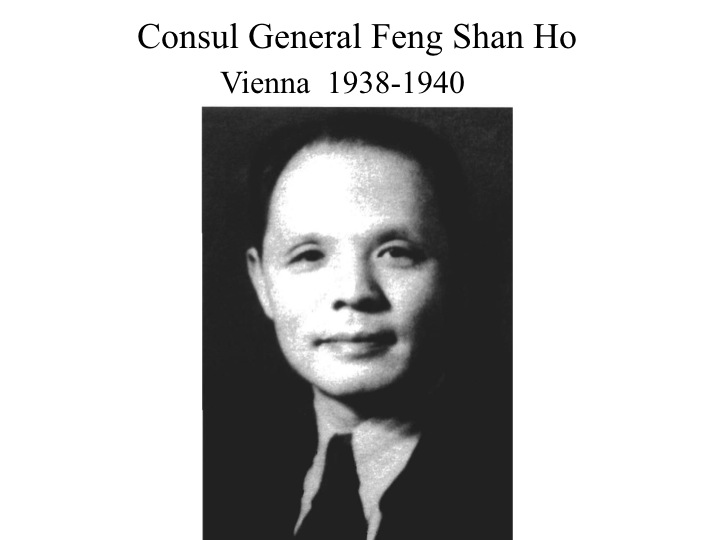

Remarkably, a few foreign diplomats stationed in Europe offered extraordinary assistance in the face of their own government’s policies. Chinese Consul-General Ho Feng-Shan, stationed in Vienna since 1937, issued thousands of Chinese visas to Jews, who lined up at his office in 1938 and 1939. These documents were not needed to enter China, but were very useful in getting the Nazis to issue passports, in convincing third countries to allow entry, or in buying tickets out of Germany.

Since anti-Jewish violence was first applied by the Nazis on a broad basis in Austria during the Anschluss, Viennese Jews were the first to seek out Shanghai as a destination for mass flight. During 1938, perhaps 1500 refugees arrived in Shanghai, two-thirds of whom were Austrian. When the families of men arrested during Kristallnacht began to arrive in Shanghai in large numbers in early 1939, the proportion changed to more than two-thirds from Germany, in line with the relative sizes of the Jewish populations of Germany and Austria. By that time, the ships of the Italian Lloyd Triestino Line, along with ships from France, Holland, and Germany, were bringing over 1000 refugees a month into Shanghai.

The trip to Shanghai typically took four weeks. As the ships passed through the Suez Canal and stopped at the largest ports in southern Asia, local Jewish communities came out to greet and support the refugees with food and supplies. The British, on the other hand, worried that refugees would escape into their colonial outposts in Aden, India, or Singapore, and tried to keep them confined near the docks or even on the ship.

Those who went to Shanghai were ordinary Jews. The wealthy and famous had international connections which made getting visas and affidavits easier. Those who went to Shanghai that year typically had nobody to vouch for them in the US, were unable to bring significant financial resources out of the Third Reich, and had no especially desirable skills. They were families of salesmen, doctors and store owners. Nazi regulations forbade bringing most valuables out of the country and limited cash to 10 Marks or $4 per person. Shanghai was an exile of the little people, ordinary Jews.

Arrival in Shanghai was a shock. Loaded onto trucks like so much baggage, the refugees were driven across the Garden Bridge to a barracks financed by generous Baghdadi Jewish families. The hallmarks of European domestic life, privacy and cleanliness, were suddenly replaced by tropical heat, bedbugs, and shared toilets.

The various national and ethnic communities in Shanghai responded quite differently to the newly arrived refugees. The Baghdadi Jewish community created a relief committee headed by Paul Komor, the Honorary Consul General for Hungary, to greet the refugees, provide temporary housing, and integrate them into the Shanghai economy. The Sassoon and Kadoorie families used their wealth and influence to smooth the descent of these Europeans into refugee status. Many Russian Jews offered assistance, but on a less-organized, more individual basis.

The American, British, and French businessmen, who ran the international zones of settlement, had little sympathy for the plight of Jews in Europe. In December 1938, when only about 1500 Central European refugees had arrived, the SMC voted to prevent the arrival of any further Jewish refugees; the Japanese, who by then controlled the port, refused to comply.

The Japanese, allies of the Nazis, were much more accommodating. Believing that international Jewry possessed wide powers, government policy was designed not to antagonize Jews. When the SMC formally requested at the end of 1938 that the Japanese help to restrict Jewish arrivals, the Foreign Ministry told its representatives in Shanghai to reject this attitude.

But German and Japanese officials in Shanghai, like their western counterparts, began to complain about the economic impact of the growing Jewish refugee stream, as more than 1000 Jews arrived every month in 1939. In May and June, the Japanese Consul Ishiguro repeatedly complained that Jews were taking business away from Japanese in Shanghai, and asked what German reaction would be if the Japanese restricted Jewish entry.

When the Berlin government responded positively, the Japanese moved quickly to put restrictions into effect. On August 9, the Naval Landing Party, the highest Japanese military authority in Shanghai, sent a letter to the Jewish relief committee announcing that no further refugees would be admitted to Hongkou after August 21. The SMC followed on August 14 with a similar announcement that European refugees would no longer be permitted to enter the International Settlement.

The Shanghai door had been effectively closed for the hundreds of thousands of Jews remaining in the Third Reich. After August 21, 1939, about 1100 more refugees arrived on boats which were already underway or about to leave. The flow of 1000 per month dwindled immediately to a few hundred over the whole next year.

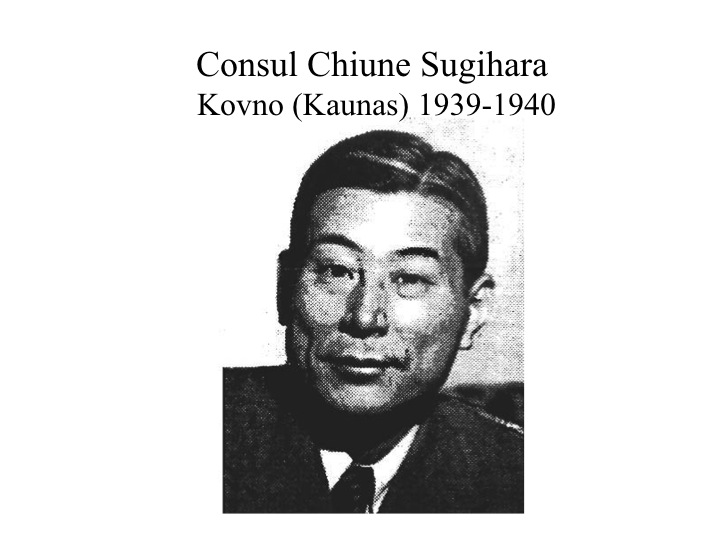

One more sizable group of eastern European Jews reached Shanghai. After the German and Soviet armies divided up Poland in 1939 and the Soviets began to move into the small Baltic countries, Jews in Lithuania discovered that the Japanese Consul, Chiune Sugihara, and the Dutch Consul, Jan Zwartendyk, were willing to issue visas for Japan and Curaçao.

Brandishing these papers, over 2000 Jews were able to cross the Soviet Union in 1940 and 1941 on the trans-Siberian Railroad, and land in Kobe, Japan. A substantial number of the Polish Jews were male yeshiva students, including the entire Mirrer Yeshiva.

Eventually they were sent to Shanghai and allowed to settle in Hongkou. The difference in attitude toward Jews between the Germans and the Japanese could not have been clearer. About 18,000 Jews had managed to get to Shanghai from Nazi-controlled Central and Eastern Europe.

Even after escape from Europe to Shanghai became impossible, the development of the war into a world-wide conflict continued to have a direct impact in the refugee community. At the same time that Japanese warplanes bombed American ships in Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Japanese military marched into the Western enclaves of Shanghai and took complete control of the city. The American and British businessmen who had enjoyed all the benefits of colonial domination lost their jobs and eventually their freedom. The Japanese set up internment camps for enemy aliens. Yet Jews from the Third Reich could continue their lives unimpeded, as long as they acknowledged Japanese dominance.

III Shanghai Exile

The 16,000 German-speaking refugees were soon sorted into three broad economic classes by the shock of expulsion from Europe and flight to China. Those who managed to bring a few dollars or some valuables to Shanghai could rent apartments in the International Settlement. For the early arrivals, it was still possible to find jobs or open businesses. A second group of families fell into poverty, squeezed into one room in Hongkou, and survived by selling their possessions and eating one meal a day provided by local Jewish relief organizations. A third group, about 2500, had nothing, and spent their Shanghai years in barracks rooms at the so-called Heime. These five complexes housed mainly men who were alone, but also many families, in huge common rooms. Most of the funding was provided by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and by local Baghdadi and Russian Jews.

Exile life in Shanghai brought out two powerful strands of refugee culture. Although many families had not put much energy into being Jewish in Europe, the Nazis forced them to consider their Jewish identity. Jews from all over the world, especially from Shanghai and from America, came directly to their aid. Jewish institutions and forms of self-governance were developed by refugees. As in Germany, the Jüdische Gemeinde (Jewish Community) was founded to include the whole spectrum of religious observance.

Within a few months of landing, the Austrian Jews created a café life on the streets of Hongkou. The few experienced theatrical professionals gathered over 200 artists around them, and organized dramatic ensembles and artistic societies. By late 1939, theater productions appeared monthly. Newspapers appeared, notably the Shanghai Jewish Chronicle published by Ossi Lewin.

Probably the most ambitious creation was the so-called Kadoorie School. When refugee children overwhelmed the existing Shanghai Jewish School in the International Settlement, the community was able to lease a vacant building in Hongkou from the SMC. In November 1939 the Shanghai Jewish Youth Association School began classes with financial support from the Baghdadi community, especially Sir Horace Kadoorie. About 600 students attended a mixture of religious and secular courses taught in English by refugees, modeled after Jewish schools in Germany. In January 1942 the Kadoorie School moved to a better site, a building which is fondly remembered by its former students.

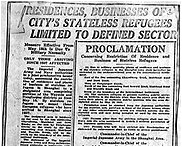

Nazi emissaries constantly attempted to convince the Japanese to kill the thousands of Jews under their control. Wild schemes were proposed, such as putting all the Jews of Shanghai onto boats and then sinking them at sea. For reasons that have not yet been fully explained, on February 18, 1943, the Japanese authorities issued a Proclamation which forced all “stateless refugees” who had arrived after 1937 to live within less than a square mile in Hongkou. About 8,000 Central European refugees who lived outside of this district had to move within three months. The February Proclamation showed the ambivalent nature of the Japanese attitude toward the Jews so despised by their German allies: the word Jew was not mentioned in the Proclamation and the existing Baghdadi and Russian Jewish communities in Shanghai were not affected.

Beyond confinement, there was little anti-Semitic content in the creation of the Designated Area. Jewish religious services were unhindered and Japanese officials occasionally attended them, watched refugee soccer games and visited school classes. Most important, Jews in Hongkou were not physically brutalized. Jews could apply for passes to leave Hongkou, although Kanoh Ghoya, the Japanese gate-keeper for Jews seeking daily passes, was notorious for his outrageous and unpredictable behavior.

Germs were much more dangerous to refugees in Hongkou than the Japanese. Close physical contact, inadequate clothing, and an ever poorer diet made the refugees susceptible to dysentery, scarlet fever and tuberculosis. About 10% of the whole community died in Shanghai, mostly in the difficult years from 1943 to 1945.

The long-awaited end of the war in Europe brought little relief to refugee families in Asia. German surrender on 8 May was welcome, but it didn’t change Jewish lives in Shanghai. The Pacific war still dragged on, but the occasional appearance of American planes over Shanghai beginning in 1944 was greeted with cheers. On July 17, 1945, American planes accidentally dropped bombs on refugee houses run by the Russian Jewish relief organization in the Designated Area. The death of about 30 refugees was a unique tragedy during the years of Shanghai exile.

After the Japanese surrendered on August 15, the ghetto barriers disappeared and suddenly there was more food. The American military brought Army rations and CARE packages, and a way of life that seemed to promise freedom and equality. The US military hired about 1500 refugees in a wide variety of jobs at high pay.

Soon more direct relief arrived. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration brought immense quantities of basic foodstuffs and clothing. The Joint invested money to improve the Heime and opened a Jewish Community Center at the Kadoorie School. Sports competitions, Boy Scout troops, and theater and musical productions were revived and expanded.

But the inflation which had developed at the end of the war worsened in 1945-47 and then skyrocketed in 1948 and 1949. Even more worrisome was the civil war between the Communist Red Army and Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government, which broke out once the Japanese were defeated.

IV The Dissolution of the Shanghai Jewish Community

Nearly all refugee families wanted to leave Shanghai as soon as possible. Very few had been able to create a life they wanted to continue in China. Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government expressed hostile attitudes toward the Jewish refugee community, and Mao’s Communists were an unknown threat. All three Jewish communities began the search for new homes.

America was the most popular destination. Many refugees had tried to get into the United States before the war, and now even more had relatives there. The possibility of a Jewish state in Palestine attracted those refugees who were more committed to their Jewish identity, along with many from the Baghdadi and Russian communities. A minority of refugees among the older generation decided instead to go back to Germany or Austria.

One year after the war’s end, only about 600 refugees had succeeded in leaving for the United States, and about half of those were Polish Jews connected to the Mirrer Yeshiva. About the same number had succeeded in getting to Australia. Relatives were able to bring a few families to Canada and Latin America. The Western democracies maintained those restrictive immigration policies which had forced Jews to scatter all over the world. By January 1947 only one-fifth of the refugees had left.

The refugees’ struggle to convince the victorious Allies to allow them to leave Shanghai finally was rewarded in May 1947, when the Allies agreed to allow entry to Berlin and Vienna. Thus the first mass exodus from Shanghai was back to Germany and Austria, the voyage of the “Marine Lynx” to Naples with 650 refugees in July 1947.

Gradually the Western democracies recognized the needs of the Shanghai refugees. By the end of 1948 nearly 10,000 refugees had left Shanghai, with thousands still seeking a way out. About 1500 went to Germany and Austria, 6000 to the US, and 1000 to Australia, but a mere 150 to England and only 25 to Canada. A few hundred were able to enter Latin America, especially Bolivia and Chile.

As the British effort to keep control of its Mandate in Palestine faltered, prospects for travel to the Middle East improved. Although the nation of Israel was officially declared in May 1948, fighting between Jews and Arabs continued into 1949. Eventually in late 1948 and early 1949, a series of ships brought thousands of Russian and Baghdadi Jews and some Central European refugees to Israel.

The civil war in China heightened the desperation of those trying to get out. The Communists entered Shanghai triumphantly in May 1949, at which time about 2000 Central Europeans were left. The new government welcomed the contribution of skilled Europeans who were willing to stay, but in the long run it was no more hospitable to these remnants of colonialism than the Nationalists had been.

Gradually the few hundred remaining Jews died of illness or old age, or managed to leave. By the time that the Cultural Revolution began to wipe out all traces of foreign influence in 1966, the Jewish communities of Shanghai were just a memory.

Today, however, Shanghai is home to a thriving ex-pat Jewish community and municipal authorities have perserved a section of the Hongkou ghetto, dedicated a memorial marker, and restored the Ohel Moishe Synagoguge as a historical museum.

Adapted by Steve Hochstadt from his book Shanghai-Geschichten: Die jüdische Flucht nach China.

REFERENCES

Ernest Heppner, Shanghai Refuge: A Memoir of the World War II Jewish Ghetto

Steve Hochstadt, Exodus to Shanghai: Stories of Escape from the Third Reich

David Kranzler, Japanese, Nazis & Jews: The Jewish refugee community of Shanghai, 1938-1945

Rena Krasno, That Last Glorious Summer 1939: Shanghai – Japan and Strangers Always: A Jewish Family in Wartime Shanghai

Maisie J. Meyer, From the Rivers of Babylon to the Whangpoo: A Century of Sephardi Jewish Life in Shanghai

Marcia Renders Ristaino, Port of Last Resort: The Diaspora Communities of Shanghai

Category: China, Minhag Bavel